Most of us boil an egg for breakfast. Not Dave Arnold, director of culinary technology at The International Culinary Center in New York.

Arnold is cooking that egg in a circulating water bath at a specific temperature a couple of hundred times over and over to make magic for inventive chefs. His eggs may be elastic or creamy or melting. This inventor and culinary tech expert is the go-to man for the chefs on New York's innovators list. His egg-cooking chart appeared in Lucky Peach magazine.

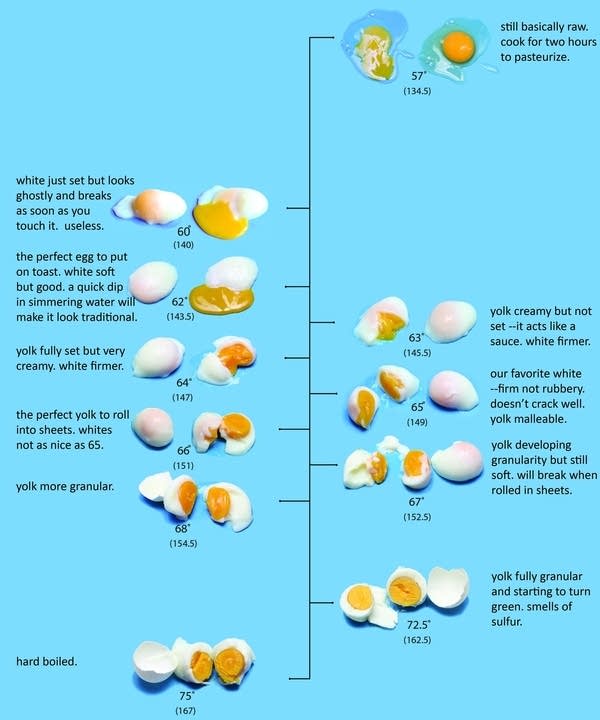

Lynne Rossetto Kasper: I saw your egg chart in Lucky Peach magazine, which has photos of a series of 11 cracked-open eggs, and each one has been cooked at a different temperature. Why did you do this?

Dave Arnold (Jeff Elkin Photography)

Dave Arnold (Jeff Elkin Photography)

Dave Arnold: A number of years ago when I made that chart, there wasn't really a lot of information available yet on the Web about how eggs performed at different temperatures. One of the biggest movements in cooking over the past 10 years has been the use of precise temperature control, or as we call it low-temperature cooking. Many people think about sous vide -- it's all under the same umbrella.

We sought to figure out exactly how eggs behaved. The easiest way to do that is to just do them at every different temperature, repeat the test multiple times, document it, and then put it out there so that anyone who wants to know how to achieve a particular result can do so.

LRK: How exactly did you cook the eggs?

DA: I took three different immersion circulators -- an immersion circulator is a piece of equipment that can maintain very accurate water temperatures, typically within a tenth or a couple of tenths of a degree -- and cooked eggs for an hour at whatever temperature I wanted to investigate, pulled them out, lined them all up, and cracked them all out. That was it. We'd already determined with a bunch of experiments that an hour was a good place to start.

LRK: These eggs really take on very different characteristics than we're used to seeing in cooked eggs such as soft-boiled, medium-cooked or hard-cooked. What have you discovered? Give me some examples of the differences in how they looked, tasted and their textures.

DA: When you're using extremely precise temperatures, you can get the white of an egg to set up into a very nice, not at all rubbery, custardy white -- it's perfectly formed. You cook it in the shell, by the way, and then you crack it out and the white is preserved. If you have extremely accurate temperature control, you can produce a yolk that is uniformly creamy on the inside. It's something that you can't possibly achieve normally.

Normally in a nice soft-boiled egg, there will be a little bit of the yolk that's basically fully set and the center will be runny. But in these eggs, the yolk almost becomes a uniform sauce that can bleed out. That temperature is right around 146 degrees Fahrenheit. Two degrees lower than that, 144 degrees Fahrenheit, and your egg yolk is completely runny like you would use for a Benedict. A mere two degrees higher than that, up at 149 degrees Fahrenheit, the yolk is completely set. It's still very soft, but it's completely set. So the entire window for an egg yolk, between runny and completely set, is only in Fahrenheit 3 or so degrees.

LRK: There's a point where you can actually take the egg and roll it out like a sheet of pasta?

DA: Sure, in the range between 149 and 152 degrees Fahrenheit you have what we call the Play-Doh egg. In that range the egg is malleable and you can almost shape it like marzipan -- you can roll it out.

Dave Arnold's egg chart, which appeared in Lucky Peach

Dave Arnold's egg chart, which appeared in Lucky Peach

LRK: How are chefs using some of these eggs?

DA: When I first started doing this, I had an extremely well-respected by everyone (and by myself) old-school French chef who quipped that it takes me an hour to cook an egg, whereas it only took him 3 minutes to cook an egg by poaching. That's true.

However, I can cook 200 eggs in that same hour. Every single one is going to be exactly identical with every other single one. I can keep them hot for service, which means I don't have to reheat them when the time comes, so it's incredibly fast to serve them out. I will never ever serve an egg that is either cold in the center or has been over poached so that the yolk is set, which is a classic problem with poached eggs.

Ninety percent of the eggs that you're going to have in a circulator in restaurant, 90-95 percent of them are all going to be cooked at about 144 degrees Fahrenheit, which is a runny egg. Every single one will be hot and every single one will be safe because they've been pasteurized by the cooking procedure. You're dealing with a product that is uniform, consistent, delicious and safe. I don't really see any downsides in that. You just have these perfect-looking poached eggs. The first time you do it, you're like, “This is just a complete miracle.” You can't believe it -- it's just a miracle.

Before you go...

Each week, The Splendid Table brings you stories that expand your world view, inspire you to try something new, and show how food connects us all. We rely on your generous support. For as little as $5 a month, you can have a lasting impact on The Splendid Table. And, when you donate, you’ll join a community of like-minded individuals who love good food, good conversation, and kitchen companionship. Show your love for The Splendid Table with a gift today.

Thank you for your support.

Donate today for as little as $5.00 a month. Your gift only takes a few minutes and has a lasting impact on The Splendid Table and you'll be welcomed into The Splendid Table Co-op.