Dana Cree is a dessert devotee and author of the seriously smart cookbook about making homemade ice cream; it's called Hello, My Name is Ice Cream. Contributor Joe Yonan spoke with her about the different kinds of ice cream and the essentials for making your own summertime treats like Donut Ice Cream and Popcorn Ice Cream at your home.

Joe Yonan: It’s obvious that you are a champion geek on the subject of ice cream, so I'm going to dive right in and ask you to explain the basic types of ice cream for us.

Dana Cree: The major types of ice cream would be soft-serve gelato and then the kind of ice cream you get in a scoop shop, which is considered American hard pack ice cream, and it's a very American invention. Within that category, there are four technical categories. The first one is custard-based ice creams, which have egg in them. The second one is Philadelphia-style ice cream, which does not have egg in it; it's just made out of dairy and sugar. That style is so predominant in America that we don't even know it as Philadelphia-style ice cream; we just call it ice cream. The third style is sherbet, which are very fruit-forward ice creams that are very low in butter fat. The fourth style is frozen yogurt. These are not to be confused with the goop that is injected into your cup and topped and sold by the pound, which has its place. These are American hard pack ice creams that highlight the flavor of yogurt.

JY: These are scoop-able.

DC: Yes.

JY: One of the big questions is why do you think that the ice cream that we make at home is so often not nearly as good as the commercial stuff?

DC: We're at a mechanical disadvantage at home. Professional ice cream makers have giant machines that are able to church five gallons of ice cream in a matter of eight minutes, and the texture of ice cream benefits heavily from making it as cold as possible as fast as possible, because the ice crystals that form are very small. They in turn also have freezers to harden the ice cream in a matter of two to four hours, and at home, we have home freezers which aren't that efficient. They'll keep an ice cube frozen, but they don't necessarily keep ice cream as hard as we need it to be. There are things you can do when you cook your base, which is the liquid batter, to reduce the amount of water in your ice cream base in the first place so there are less ice crystals to form. Follow some technique steps that include curing your ice cream base overnight, which is the hardest step in making ice cream at home, because I want my ice cream right away. I don't want to wait overnight to churn it and then wait another night for it to harden.

Dana Cree

Photo: Sandy Noto

Dana Cree

Photo: Sandy Noto

JY: One of the things that you emphasize are stabilizers. What's the role of a stabilizer in keeping ice cream the way that you want it to be?

DC: A stabilizer is simply an ingredient that works to stabilize the size of the ice crystal in your ice cream, because water has a polar quality, meaning it really wants to pull together and form larger blobs of water or droplets. That'll happen in your freezer as the ice cream fluctuates in temperature, and the ice crystals will melt, the water will pull together, and then when it freezes again, the ice crystals will be much larger. Anybody who has bought a pint of ice cream, put it in the freezer, come back later and all of the sudden has icy ice cream will have seen this ice crystal enlargement. That's also the icy plague of homemade ice cream. A stabilizer is an ingredient that bonds with water so that when it goes through that freeze-thaw cycle, which is inevitable in our home freezers especially, water that melts is already bonded to something and can't join forces with other water molecules and has no choice but to refreeze as the same size ice crystal it melted from. There are several ingredients that we even have in our home pantry that can function as a stabilizer, everything from corn starch to gelatin - the original stabilizer in ice cream. It lost favor commercially around the turn of the century in favor of less expensive plant-based gums.

JY: We can't make true ice cream without a machine, can we?

DC: No. True ice cream and that texture that we get in scoop shops comes from churning in an ice cream maker, comes from freezing an ice cream base while churning, which both scrapes ice crystals off the wall where the base freezes and chops them up and makes them small and mixes them into the mix and whips air into it at the same time.

JY: I definitely want to make ice cream now. What kinds of flavors should I make?

DC: Some of the more interesting flavors that I've put in the book are popcorn ice cream.

JY: Oh, fun.

DC: And there’s a donut ice cream. Baked goods do this really incredible thing when you boil them in milk; they sponge up and become elastic, and when you puree them in a blender, they get very smooth and pudding-like, so this donut ice cream actually has a donut blended right into it.

JY: Wow.

DC: And you could replace the donut with carrot cake, or, I have a friend named Maury who did blueberry muffin ice cream that was ice cream.

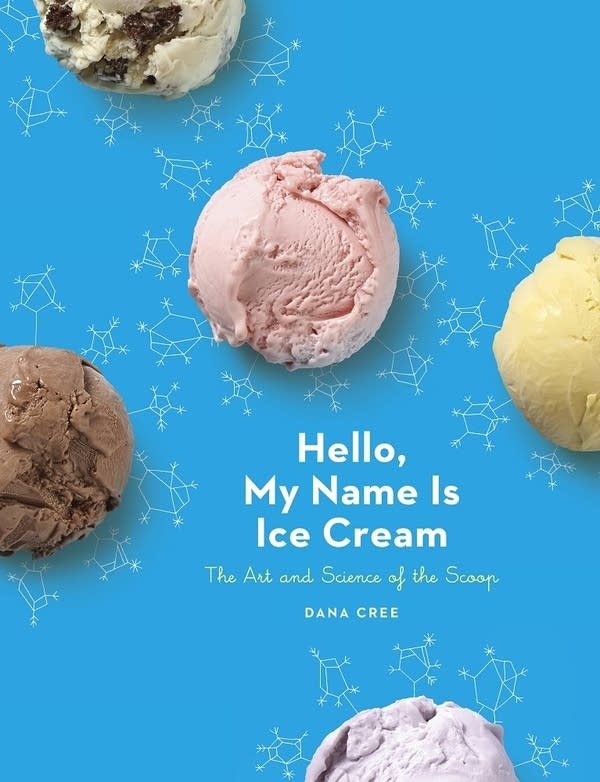

Hello, My Name is Ice Cream

by Dana Cree

Hello, My Name is Ice Cream

by Dana Cree

JY: Oh, I love it. I love it. Let's go back for a minute to the popcorn ice cream. How does that work?

DC: The popcorn ice cream was actually very challenging. When you add flavor to ice cream, you can do it in a couple different ways. You can stir something into it, in the case of a spice or a cocoa powder. You can infuse something into it by soaking the item in the milk, like you would with tea, so we tried a few different methods. I tasted it with all of the cooks who are with me in the kitchen at the time, and we all agreed it was missing something, so we tried adding butter and that just didn't quite do it. Finally one of my cooks said it's missing the flavor of the toasted oil, so we ended up popping popcorn in a pot, then adding all of the milk to it to capture that little bit of toasted oil that's in the pot, cooling the base down so that the starches didn't get gummy and then pureeing it.

JY: Oh, that's brilliant. Tell me about this crazy hay ice cream that you've got in the book.

DC: Well, you go get some hay, which is probably the hardest part.

JY: At the gardening store?

DC: I've always gotten it by going down to the farmer's market and harassing people and asking them for it. It has these incredible, green tea grassy notes, so we toast the hay and then bring the milk and cream to a boil and then add the hay in it just like you would make a cup of tea.

JY: Wow. I love that. Do you have any general rules for infusing flavors into ice cream?

DC: Yeah. Infusion is the easiest way to add flavor to ice cream. The one thing I learned, especially with fresh herbs, is you want to put more in at the beginning, for a very strong, fast infusion, so if you use basil, put more basil in than you think you need and then taste it early until you get the flavor. The longer they sit in the milk, the more they start to extract sort of vegetal bitter notes. Taste often, and if you want to add more basil, what I recommend is straining the basil or the herb out and then reinfusing with a second batch of basil.

JY: It's a reason to grow herbs in your garden, just so you can infuse them to make ice creams, it seems to me.

DC: Absolutely.

Before you go...

Each week, The Splendid Table brings you stories that expand your world view, inspire you to try something new, and show how food connects us all. We rely on your generous support. For as little as $5 a month, you can have a lasting impact on The Splendid Table. And, when you donate, you’ll join a community of like-minded individuals who love good food, good conversation, and kitchen companionship. Show your love for The Splendid Table with a gift today.

Thank you for your support.

Donate today for as little as $5.00 a month. Your gift only takes a few minutes and has a lasting impact on The Splendid Table and you'll be welcomed into The Splendid Table Co-op.